Murakami bares all in his Afterword.

This late in the game, he doesn’t have to dig deep for the metaphors. He has accomplished everything a novelist could reasonably be expected to, at least as far as popularity goes. Maybe he left a few hundred plot threads dangling. But it was part of the mystique.

This bloated novel adds to that trend, which is a dance between constraint and revelation.

His main character begins in the elegiac, dislocated reality first encountered in Hard-Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World, but he ultimately chooses to dwell in the mundane world. As the author explains, the concept for this book originated in a novella he published at the beginning of his career and immediately regretted unleashing onto the public. 40 years later, he decided enough time had passed to revisit the setting. Or perhaps his well had run dry. The pandemic bummed him out, as he explains in the last pages on the book. Walls had been constructed around the city that was human kindness – that’s my interpretation.

In any case, he spent 3 years on this fix-up novel, expanding the original, one would hope of his own volition, rather than at the behest of his agent, publishers, editors, et. al. The man is getting up there in years, and his daily marathon has taken its toll on his ability to sit at a desk for long periods.

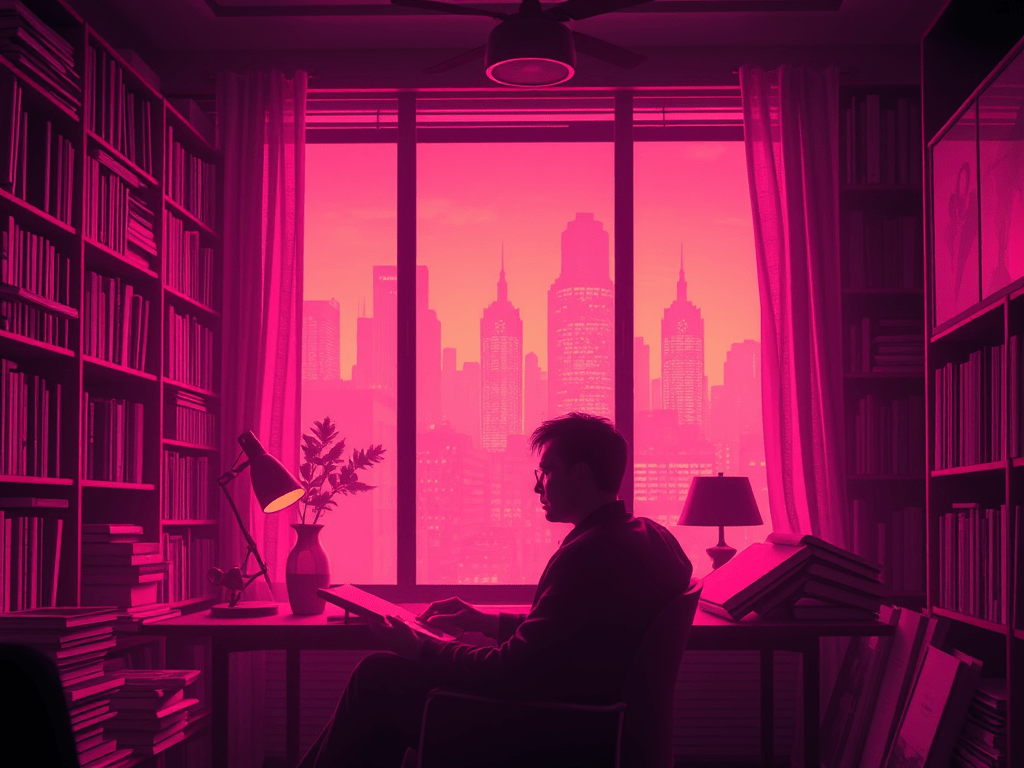

The mechanics of the book are straightforward. The plot unfolds at a glacial pace. Murakami cultivates a cozy atmosphere with firelight and the muffled comf of book-lined library walls.

Like many of his previous creations, the protagonist longs for an idealized past. He feels unfulfilled in love, but cannot bring himself to seriously commit to a relationship at this stage. He seems more married to work. But what that work is, exactly, eludes description.

He ends up being a bookish sort of person doing bookish things. He settles in a book-lined office where he meets unhurried, well-mannered people.

An inconclusive side quest ensues, where a very-bookish boy reads continuously, and our protagonist investigates this bibliophilic phenomenon.

Ultimately, as one might suspect, the tenuous connections between the mysterious walled town and the protagonist’s so-called life converge, yet what it all means is left up to the reader to decide.

It begs the question, is there actual substance here?

The guidance character, a trope, similarly inconclusive, dumps explication and then vanishes. The female love interest also provides context for the milquetoast main character, but she does not change. She has no arc, internally speaking. The flat characters perform rote tasks in a way that is both mesmeric and dull.

Murakami is at his best when he lets you inhabit a beautiful moment, where life seems suddenly precious. But the final analysis usually proves that Murakami is flying blind. Subtexts sizzle beneath the surface of these unassuming encounters. One discerns layers sometimes, but the whole doesn’t congeal, no matter how many times you puzzle out the loopy wanderings of his lost puppets.

One can only sit with the enigma and savor brief flashes of human connection within the unexplained vastness of the universe. He is a contemplative author, more often superficial than deep, but his quirky retreats into the shallows of dream and breakwaters of the subconscious are consistently affecting.

I hate to say this is one of his most boring books, but it bears all the burdensome traits of a Murakami experiment. The way Spike Jonze always calls his movies ‘joints,’ this might be called another Murakami ‘joint.’

Leave a comment