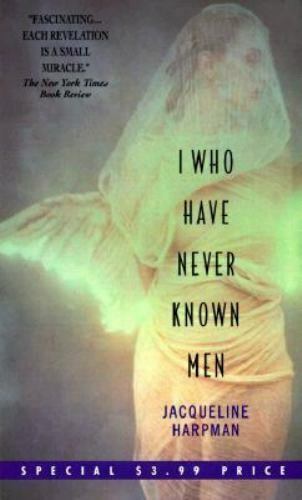

The ideal audiobook experience.

I’ve attended many workshops and critique groups which were obsessed with the “Show, Don’t tell,” mantra, which some writers seem to regard as the be all, end all rule of writing.

For me. I enjoy narration, even hundreds of pages of narration at a time. I don’t need to see a character making pasta. You can just tell me they made pasta, or better yet, cut out the whole scene and get to the story. You can keep your snappy dialogue and gesticulations. I am reminded of Robinson Crusoe, one of the first great novels of telling. In reality, much is shown by telling. And about 99.99% of books employed far more telling than showing before contemporary rules of writing took over the publishing world. By keeping the perspective close, the storytelling often shines in this book. Relying on cinematic scenes, many of which don’t accomplish any more than simple narration would have resulted in a weakening of the the taught threads composing this novel.

The narration in this book is superb. The slow and subtle recounting of another world. Like Herland and a few works by Joanna Russ, this novel is interested in describing a female viewpoint in a post-patriarchal setting. Men are out of the picture. Present like shadows in the beginning, and finally absent for the majority of the book. Their threats and control echo throughout the remainder of the tale long after they depart. Does this indicate the author suggests that a receding patriarchy will cast lingering side effects through the generations? You could ask countless poignant questions while you read, provoking a discussion with yourself if you have no one to read it with.

The simple premise, laid out in the book jacket copy, may hook you, but if it doesn’t, the first few pages probably will. The strange mentality of our narrator is the result of her upbringing in a prison-like environment, where her comrades remember another world before confinement. None of them can explain how they got there, but they have theories.

The setting shifts from one type of survival story to another. The less you know going in the better.

I found it riveting like few other books. Simply listening to the main character’s thoughts, which are stilted by her and lack of stimulation, one might say lack of development, inherent in her internalization. She posits new ways to measure time without reference to the sun or any sign of technology by counting heartbeats. She uses the resources at her disposal, including the knowledge of others. Her moral strictures are not ruled by religious dogma or desperation. She knows only the facts of the present, having a blank past, uncolored by history. Robinson Crusoe had his Christian morals, but the main character here is a true alien amid inhuman ways of living.

The system in which they are trapped operates through arbitrary-seeming and utterly mystifying illogic. The world-building will leave you itching to explore throughout.

Much discussion could be had about the author’s intent, which may prove elusive to some readers. Why keep the story so unremittingly bleak, why leave so many dangling unanswered questions? It was so we could go on thinking about the world and this character forever, dreaming and feeling what she must have felt. The uncanny realism of the beautiful narration makes me relieved and glad that this read more like a diary or a tale told around a campfire, not like scene by scene interactions which break tension into variant pacing. I’d love to see more translations of the author’s work, and take heed, the next time you hear someone tell a writer in a high-pitched voice “You know what they say, SHOW, don’t tell,” please give that person this book.

Leave a comment