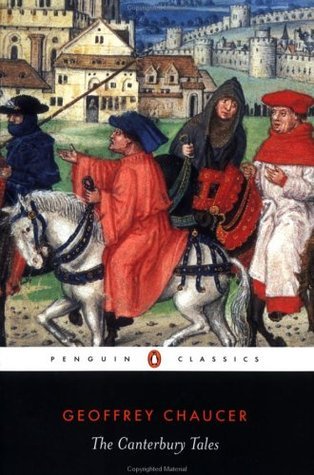

While not as approachable as high school teacher’s would have you believe, the Canterbury Tales is an entertaining mix of history, lyricism, and satire.

In my opinion Chaucer missed a major opportunity to add a pastoral component to his work. The tales either all take place in disparate locations and times, telling of old events and veering toward the more recent recollections of his time, without going into much detail in regard to setting. But they, none of them, seem to immerse the reader in the physical universe, sounding often like people talking at you instead of immersing you in a poetic epic. I found a lot of Chaucer’s set pieces somewhat confined in contrast with the works of Dante and Homer, whose writing offer a great sense of expansive wonder.

Aside from the magnificent Prologue to the Tales, the storytellers themselves often seem like floating heads. I would have loved more interpolations, more arguments, debates between the characters and physical descriptions. The lack of description gives the poetry a more austere feel. If you can put up with five hundred pages of rhyming end lines, you will be able to return to this work with much to gain from subsequent re-readings. The original Middle English is less readable than interesting in my view. Why not smooth out your reading experience with a modern rendition? All you will be missing will be the antiquated phraseology and stiff structural differences. I am not a purist when it comes to Chaucer, though I will be hard-pressed to get into his other works like Troilus and Criseyde. I can only take so much Middle English before I tire of rearranging words and meanings to render them intelligible. You could puzzle your way through the manuscript if you want to brag that you read it in the original, but nobody is going to be impressed. It is a distracting way to read until you become so proficient in it that you can do it without thinking. Which I do not have the patience for.

Similarly, I am loathe to start Spenser’s Faerie Queene for the same reason, but I know I will eventually relent. Medieval works of the imagination hold a special place in my heart, and I would love to delve more into similar epics.

As for my favorite tales, I really enjoyed the Prologue, the Knight’s Tale, and the Canon Yeoman’s Tale. I would have liked to see more chivalry, alchemy, and ribaldry, and less squabbling between wives and husbands. Chaucer apparently had a lot to say about the roles within the bonds of matrimony. Like literary fiction today, adultery is an endless topic in fiction/ poetry, one writers never seem to tire of describing ad nauseum. I recommend giving this a try if you were exhausted by sections of it in school or were forced to resort to Cliff’s notes. The poetry is engaging in places, and the message always devout, even when the scene described is rather crude. He started a fun contest between two of his storytellers, where one disparages the other in his tale and the other responds by criticizing the other’s profession in his. I would have liked to see more of this intertextuality, like a call and response between the participants of the tales, rather than straight, uninterrupted storytelling. Considering that legends and folklore were rife in other medieval works, Chaucer seemed too squeamish to mingle demons and faeries into his stories. He was more concerned with the mundane details of ordinary life, which bookend most of the tales. Occasionally something violent happens, and someone loses a head, or someone gets mooned, and the devil makes a brief appearance, but after a few hundred pages, the characters telling the Tales all blend together. The Prologues introducing each should have done more to develop the characters, to alleviate some of this blurring lines between their personalities. But perhaps I approached the work from too modern a perspective. I find it strange he called it Canterbury Tales instead of Canterbury Poems. There were other collections of prose tales and oral tales at the time, and they were not all poetic in nature. But this was before the printing press, a normal person might be lucky to come across five authentic manuscripts in a lifetime I would think.

Today we have the opposite problem. There is too much text, too many books, and the literature we have access to, along with the myriad commentary, reviews and criticisms, make it impossible to digest the culture of today or assign values to it. What is good literature anymore? What is worth preserving? We seem ready to preserve every Tom, Dick, and Harry’s cooking blog, and every angsty fanfiction ever written in the heat of bed-wetting adolescence for the sake of a posterity which is wholly imaginary. I wonder if future generations in the postapocalyptic landscape will have to construct their shelters out of the useless books we filled up the world with during this generation because there will be no other building materials among the desiccated remnants of civilization.

A modern equivalent might be the Spoon River Anthology, which I also recommend. It would make a good college paper, contrasting these two works of poetic fiction. Makes you wonder if in 800 years people will be reading Robinson and Whitman and revering them like we revere Chaucer.

So why read Chaucer in this day and age? Because it reminds us that human nature persists, and that storytelling is an art that never dies, only changes form. Poetry is also meant to be a form of narrative art. We so often today consider poetry a way to describe feelings through free verse, subscribing to haiku brevity or the sappy sentimentality of postmodern multimedia poetry, where slang is mingled with gross intimacy to produce a quaint and vague irritant to our sensibilities. But for thousands of years people sat down and set words to meter as if language were an instrument they were playing. These constraints forced their narrative down a narrow track which carved a deep crevice through history and etches its way into the soul if you study it to extract the meaning and suck the marrow from its skeleton. I wish there were more epic poems being written today.

Leave a comment